Who belongs?

Oops

Over the past few weeks, you may have noticed something changing in the landscape of our towns and cities. On roundabouts, across zebra crossings, even sprayed onto the kerbsides, St George’s crosses and Union Jacks have appeared. For some, these are symbols of pride: expressions of identity, belonging, and loyalty. But this doesn’t seem to be how they are being used. It seems to be a movement designed to stir unease. Because they have been intended to send a message of division: a message of “you are not welcome”. … of “go away” and “go back home”. An uncomfortable, detestable – and dare I say wholly unbritish - message to see and one which diminishes our communities. A flag being used as a symbol of anger and with the intention to unsettle and invoke fear and to build barriers between people.

It reminds us that the question of who belongs is never neutral. We all long for that sense of being welcomed in, of being part of something bigger than ourselves. But we also know the pain of exclusion … of feeling that somehow we do not fit, that we are outsiders looking in.

Some of us may remember times when you were left out at school: standing on the edge of the playground, longing to be chosen for the team, but passed over every time. Others will know what it feels like to arrive at a party, or a church service, and not quite be sure if you’re really wanted. Even online, exclusion happens. Groups form, messages fly, and you discover you were not added to the chat. It is a small thing, but it stings. Because all of us, deep down, ache for belonging.

When these flags and symbols appeared, they touch this deep nerve. They whisper “We don’t want you.” And that whisper cuts to the heart of who we are.

Closed Hands

Ugh

In the passage we read from Mark’s Gospel, parents are bringing their children to Jesus. It seems such a simple thing. They want his blessing, his touch, his welcome. But before they can reach him, the disciples step in. They block the way. Mark says they rebuked the parents:telling them off for bothering the Teacher. Their hands are not open but closed.

To us, it feels harsh. Why would the disciples do this? But in their culture, children had very little standing. They had no voice in public life, no authority, no wealth, no usefulness. They were not considered important. The disciples thought they were protecting Jesus’ time. The great Teacher should not be distracted by little ones. His hands, they believed, were reserved for grown-ups: his time was for the significant, the powerful, the worthy.

And here is the problem. The disciples thought they were serving Jesus, but in fact they were shutting people out from him. They made themselves gatekeepers to the kingdom. They decided who belonged and who did not.

It is uncomfortable, but this is where the passage turns the spotlight on us. Because we too are tempted to act as gatekeepers. We might not mean to, but we sometimes put up barriers that keep others from Christ. Perhaps we overlook the young, thinking they have nothing to contribute. Perhaps we ignore the elderly, assuming their best years are behind them. Perhaps we avoid the refugee or the homeless person, unsure of how to respond. Perhaps we quietly sideline those who do not fit the way we like church to be.

Our hands, like the disciples’, can close rather than open. We end up deciding, even without saying it out loud, who belongs at the centre and who does not. And if we are honest, all of us have done this. We know what it feels like to be on the inside, and unfortunately we also know how easy it is to push others outside too.

Open Hands

Aha

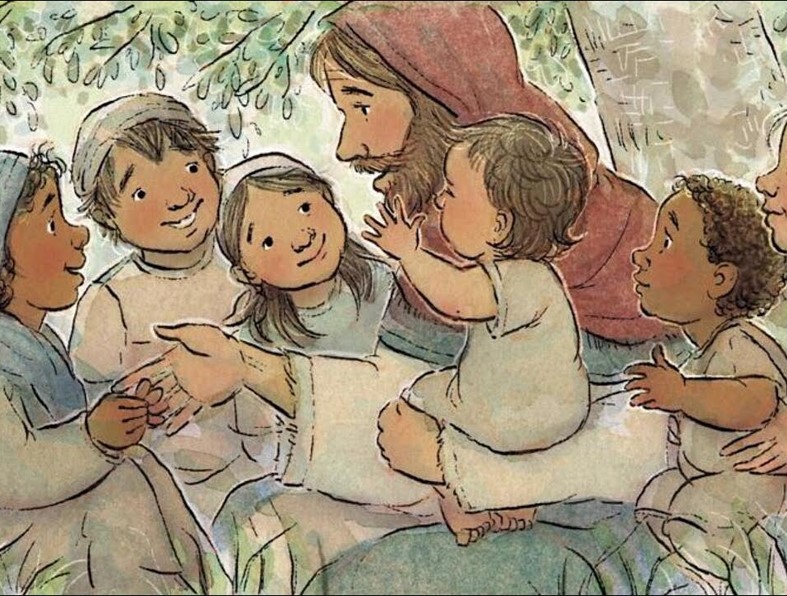

The disciples’ hands are closed. They push back, they keep out, they rebuke. But Jesus’ hands are different. Mark tells us that when Jesus saw what was happening, he was indignant. That’s a strong word. He was angry. This wasn’t a minor irritation: this was a violation of the kingdom and a rejection of its values. And in that moment, Jesus overturned their assumptions.

“Let the little children come to me,” he said, “and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these.” And then, in one of the most tender scenes in all the Gospels, Jesus gathers the children in his arms, places his hands on them, and blesses them.

Think about it. These were children who, in the eyes of society, didn’t count. They had nothing to offer, no power, no influence. Yet Jesus makes space for them at the very centre of his kingdom. His hands are open. His embrace is wide. His blessing falls on those who had been pushed aside.

This is what the kingdom of God looks like. It is not built on status, or power, or usefulness. It is built on welcome. It is marked by radical hospitality. And if we are honest, that is good news for us too. Because as we stand before God, we bring nothing of worth. We cannot buy or earn his favour. We come empty-handed. And still, Jesus welcomes us. Still, his hands are open to us.

Welcomed by Christ

Whee

The picture we see in Mark’s Gospel is not only about children two thousand years ago. It is also about us. For the same hands that held those children would one day be stretched wide on the cross, opening to embrace the whole world. Jesus’ hands bless and welcome. His hands make space for us all.

Think for a moment about those children. They were powerless, unnoticed, overlooked. They had nothing to offer. And yet Jesus gathered them in his arms. He laid his hands upon them and blessed them. His welcome was not about what they had achieved, but about who they were. They belonged simply because he loved them.

That is the shape of the kingdom of God. And that is the shape of the Gospel. Because when we come to God, we too come empty-handed. In fact, if we are honest, our hands are often stained with failure and sin. And yet, like those children, we are drawn into the arms of Christ. His hands are open for us.

And this is not just a passing gesture of kindness. For Calvary declares that his hands remain open … not just to a few, not just to the worthy, but to the whole world. On the cross Jesus took into his own hands all that shuts us out - our sin, our shame, our failure - and he dealt with it once and for all. His hands bore the nails so that ours could be set free. His arms opened wide so that we could finally belong.

And so when Paul tells the church in Corinth, “You are the body of Christ” he is making the point that he welcome of Jesus has not ended. His hands are still open … but now they are open through us. His church is called to be his body in the world. Which means that the welcome we have received must become the welcome we extend. The belonging we have tasted should become the belonging we offer.

So here is the Gospel: You are welcomed by Christ. You are held in his hands. You belong. And now, as his body, we are called to become those same hands of welcome in the world

As His hands did ...

Yeah

So where does this leave us? What difference should that make to us this week?

Being the body of Christ is not merely a metaphor to be admired: it is a calling to be lived. So let’s make this very concrete. I want to suggest three simple movements:

Who is God calling you to welcome? There will be someone. A neighbour you usually pass with a nod but never really notice. A colleague who is always left out. A refugee family in your community. A teenager who struggles to fit in. Ask God to put one face, one name, in your mind even now.

How can you make space? Open hands are more than a warm feeling. They are gestures, actions, invitations. A phone call, a meal shared, a listening ear, a seat saved beside you. Small acts of openness that say: “You belong here.”

What will you do this week? Not in theory, but in practice. One act of welcome. One step of blessing. One open-handed gesture that takes the welcome of Christ you have received and extends it to another.

I invite you to open your hands right now. (Pause) Look at them. These are Christ’s hands in the world today. Through them, his welcome is offered. Through them, his blessing is shared. Through them, the least, the overlooked, the powerless, may know that they belong.

So let this be our refrain: As Jesus’ hands did, so we too must.