The Hand That Heals

Gt

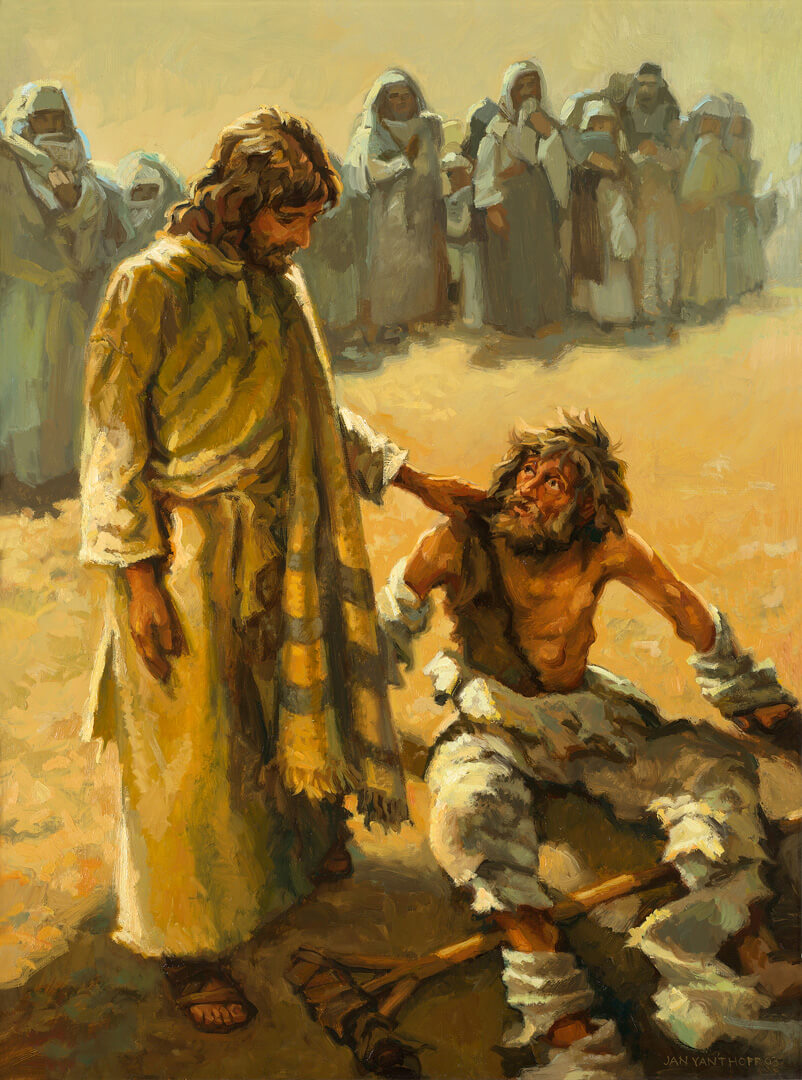

Picture the scene. A man, covered with the marks of leprosy, dares to approach Jesus. His skin is diseased, his clothes torn, his voice hoarse from crying “UNCLEAN!” to warn others away. He kneels before Jesus, desperate, uncertain, vulnerable. “ ” What happens next is pure grace. Before anyone can push him back, before the crowd can tell him to keep his distance, Jesus stretches out his hand. He does not recoil. He does not hesitate. He touches the untouchable. And in that moment, something extraordinary happens. The leper is healed. His skin becomes fresh, his body restored. But there is more here than the repair of broken flesh. This is also the restoration of community. The man once excluded is welcomed back. The one pushed to the margins is brought into the centre again. Healing here is not just medical—it is social, spiritual, human. Notice carefully: the miracle is not only in the power that flows from Jesus, but in the compassion that moves him to touch. A touch that says, “YOU ARE NOT REJECTED. YOU ARE NOT FORGOTTEN. YOU ARE LOVED.” The grace of God in Christ is seen not in distance but in closeness, not in avoidance but in embrace. This is what divine holiness looks like. Not cold separation, but warm, barrier-breaking compassion. Jesus does not catch impurity from the leper; the leper catches healing from Jesus. His grace overturns fear. His love restores dignity. And his hand … his hand that reaches where no other hand would dare … is the hand of God reaching into human shame.

Healing That Continues

Gw

That same grace has not stopped with the first century. The healing touch of Jesus continues today: not always in miraculous cures, but in countless acts of compassion that restore dignity, reconcile the excluded, and bring wholeness where there was once shame.

Think of the ways this happens in everyday life. A nurse takes the hand of a patient who is frightened and alone. A Salvation Army officer sits beside someone in prison, offering presence and hope. A neighbour invites the lonely man next door in for a cup of tea. These are not dramatic moments for the history books, but they are moments when the hands of Christ are at work in the world.

Grace is revealed in small, ordinary touches. When a meal is shared, when forgiveness is extended, when someone listens with patience, we see the continuation of Jesus’ hand reaching out. Holiness is not only about rules or boundaries: it is about embodying God’s love in such a way that people once labelled “unclean” discover they are welcomed and cherished.

The church, Paul reminds us, is the body of Christ (1 Cor 12:27). That means his hands are now our hands. His touch must be felt in and through us. When we act in compassion, it is not merely our kindness but Christ’s own healing presence flowing through his body.

And this is why the church is more than an institution or a building. It is a living body that extends the touch of Christ into the world. Every time you or I stretch out a hand of kindness … every time we risk compassion instead of retreat … his grace is at work. The healing power of Christ continues whenever we dare to touch those the world keeps at arm’s length.

The Scandal of Touch

Tt

To understand how radical Jesus’ touch was, we must remember the world he moved in. Jewish purity laws structured life. They marked the boundaries of worship and community, and those boundaries were meant to define holiness. Lepers were declared unclean, and that declaration carried real consequences. They were excluded from synagogue worship, from family life, from the rhythms of everyday belonging. They bore a public stigma that made them visible examples of what the community must avoid.

So when Jesus reaches out, he is doing more than offering a medical miracle. He is confronting a religious system that preserves itself by pushing others away. The probable reaction of the crowd would have been horror. To touch a leper was to risk ritual defilement. To associate closely with the unclean was to court censure. Jesus’ touch was a prophetic action, a visible denunciation of a piety that protected status at the cost of love.

This provokes an uncomfortable question for us. Are there ways in which our own rules, however well intentioned, function to protect our sense of holiness while leaving the vulnerable on the outside? It is not hard to imagine. We make membership lists, reserve the front row for the respectable, design ministries that require neat paperwork and punctuality. In these arrangements some people simply do not fit. Religious systems can become walls rather than gateways.

The gospel text levels a critique against such systems. True holiness is not preserved by boundaries that exclude the suffering. It is enacted in the costly proximity of compassion. Jesus chooses scandal. He chooses relationship over reputation. He renounces the convenience of keeping distance. The leper’s restoration is therefore an indictment of any practice that confuses holiness with separation.

There is also a personal dimension in the text worth noting. The leper does not demand; he asks with vulnerability. His conditional plea, “If you are willing,” exposes the deep human fear of rejection. Jesus’ immediate answer, “I am willing,” is therefore the heart of the gospel. It names divine consent to enter our shame. That consent is costly because it embraces what we would rather avoid. When we receive that consent, we are called to embody it. The theology of the incarnation is practical. God has not left us as detached lawgivers; God has become flesh and entered our mess. Therefore discipleship requires us to be willing in the small and costly moments of neighbourly presence.

So the scandal remains. The church is called to hazard its reputation for the sake of mercy. If we find it easier to stand aside than to step in, then we need to repent. The is a mirror which forces us to ask whether our holiness protects the marginalised or whether it protects ourselves: do we choose the costly path of compassion, even when it looks scandalous to the world?

Our Resistance to Risky Compassion

Tw

The scandal of Jesus’ touch is not merely a curious historical note. It exposes a pattern that persists among us. We are adept at inventing reasons to keep distance. Sometimes they are practical. Sometimes they are spiritual. Sometimes they are about reputation. In combination they form a barrier that prevents us from extending the very healing we proclaim.

Consider some everyday realities. Addiction carries shame, and churches can be quick to judge rather than to accompany. Mental ill health is often misunderstood, and many congregations lack the training to be present. Ex-offenders struggle to find welcome. Homeless people are politely ignored rather than invited in. The reasons may vary but the effect is the same: people remain on the margins where their dignity is eroded.

There are also institutional forces at work. Programmes and policies, while necessary, can inadvertently screen out the messy work of pastoral presence. Welcome teams may be excellent at arranging coffee, but less prepared to sit with grief. Safeguarding rules are vital, and must be followed, but they should not become an excuse to avoid relationship. We need both wise boundaries and bold compassion.

So what might a church that embodies Jesus’ scandalous grace look like? First, it needs a theology that places proximity at the heart of holiness. We preach and teach a God who enters suffering, not a deity who stays aloof. Second, we need practices that cultivate presence. That could mean training volunteers to listen well, creating visiting teams for local hospitals and prisons, or redesigning services to make space for lament and testimony. Third, it means resourcing those who do pastoral work, ensuring they have time and support to sustain difficult ministry.

Practically, congregations can begin by naming the discomfort and training for it. Leadership matters here; when church leaders model messy mercy, others follow. Enable small groups to engage with local agencies, encourage members to volunteer with hospices and addiction services, and create clear pathways for people to tell their stories without fear of judgement. Celebrate the risks taken and the small wins. When compassion is normalised, it becomes contagious, and the church begins to reflect more faithfully the scandalous grace of Christ.

We also need realistic expectations. Compassion is not efficient, and it is not always successful in producing cure. But it does restore dignity. A shared meal, a steady visitor, an offer of practical help—these gestures matter. They signal that a life has value, that a person is seen. In chapels and kitchens, in hospitals and hostels, the hands of Christ can still be at work.

Finally, there is risk. Reaching out may invite criticism. We might be misunderstood. We might fail. But the alternative is comfortable irrelevance. Better to be criticised for compassion than commended for keeping pristine distance. So let us practise risky kindness. Let us train our hands to reach. As Jesus’ hands did, so we too must reach out, touch, restore and bear the cost of compassion in the world.

Conclusion

We have seen today how Jesus reached out his hand to the leper — a hand that healed, a hand that restored, a hand that scandalised the crowd. We’ve seen that same grace still at work in the world through ordinary acts of compassion. And we’ve faced the troubling truth that too often we, like the crowd, resist the risks of touch and settle for safe distance.

It is tempting, especially in an online gathering, to let these examples feel like they belong to other churches, in other places. It’s easy to say, “YES, THE WIDER CHURCH NEEDS TO DO BETTER,” and then quietly move on. But the Word of God today is not addressed to someone else. It is addressed to us. What about our church? What about me? What about you?

We cannot lay hands on one another through a screen, but we can still decide whether our community will be known for risky compassion or for safe distance. We can ask: How will we embody the touch of Christ where we are? Whose shame will we cross to stand alongside? Whose loneliness will we step into?

The call of Christ is not to a comfortable discipleship but to a costly one. To be the hands of Jesus in the world is to be willing, as he was, to pay the price of compassion.